Little women and philosophies

The last month of 2016 saw 3 more books added to my Goodreads’ collections. And since this blog has not a single book review, it is perhaps the right time to jot down a few notes on these very interesting pieces of literatures.

Little women

A whimsical gift directly from the Bodleain library of Oxford, it is a delightful 800-page portrait of a family of 4 women. I couldn’t have guessed that the author, Lousia May Alcott, was an American, and that the book was based somewhere in the States. Well, at least not until half way through the book. The blend of Dickens and Austen were palpable throughput the book. There were caricatures of characters, there were the humors very characteristic of Dickens. At the same time, female protagonists, frivolous matters of dress, propriety and finding husband, are unmistakably Austen. In fact, the more the plot develops to focus on Jo March, the easier it is to draw comparison with Emma and Lizzie. They are modelled as progressive women who were at first against marriage, or at least traditional notions of marrying for fame and for money; but who inevitably came to senses and were married before the book ends. Of the three women, Jo is the least annoying, for she is truly talented and does try to make a career for herself (unlike Emma and Lizzie, who I have no idea what they do professionally). I feel it strange when progressive female characters do not have a career aspiration, or a professional interest other than housekeeping and making a good wife. They are ahead of their time, demanding more freedom for women, but not far enough as to having independent careers (though of course I am projecting from a very far future where such progressiveness are the norms).

Having no cliff hangers, no surprises in character developments, Little Women is compelling enough to get me through few dozen pages per one read. No cliff hanger does not mean dull plots, and Alcott’s alternating between a handful of subplots makes it refreshing. And the simple, yet eloquent writings, beside adding adding a fitting, womanly air to the content, help turning the book into an enjoyable read. Foreign readers like me (who are not native English speakers), appreciate books that demand little cognitive exertions in parsing and reconstructing complex sentences. If fiction is like a house, words and sentences are like corridors and stairways that help us readers navigate the interesting parts of the house: the rooms. Sometimes simple pathways are brightly illuminated, sometimes they are even accompanied by music and artworks. And these are great bonuses. But as soon as they are turned to a maze, asking readers to scramble around blindly for direction, the house loses its appeal. Thus come a habit that before buying a book, I would flip a random pages and read a few sentences to gauge how easy they are to read.

Problems of philosophy, and the gay science

Going from a classics fiction to a contemporary non-fiction almost always gives me dizziness. Especially going from everyday-life matters to philosophical matters. The latter include highly abstract subjects concerning knowledge, perception, consciousness, morality and religion. Is it not fair to say that philosophy is stranger than fiction?

I started with Bertrand Russell’s Problem of Philosophy, which was recommended as an easy introduction to Russell’s philosophy. This little introductory text already comprises 100 pages, and in completing it I glanced at The Writing of Bertrand Russel’s massive volume of small text with no small foreboding. Widely regarded as the most important philosopher of the last century, Russell left his mark in mathematics and especially in logics. His influence is also felt in the development of computer science, with Godel’s incomplete theorems and all other logic paradoxes that inspire Alan Turing. His writing, however, is decidedly academic. Reading his summaries on problems of modern philosophy, one cannot help but imaging a breaded man rambling about far-fetched and inconsequential topics. Like an academic paper, the first parts of each essay, where he poses the questions, are compelling. But the interest dies off only a few sentences latter as the author seems to be lost in his own explanations. He appears to be overwhelmed by how much details that he wants to cover, and goes on to enumerate as many as possible. This style of writing fits only audience with some backgrounds on the topic. That said, the book is outstanding in bringing the values and the essence of philosophy to light:

-

The book’s very first sentence, which poses the question whether there exists knowledge so certain that no man can doubt it, captures perfectly the core of philosophy. It then goes on with an example of asking whether a table one sees and feels really exists, and if it does, what exactly is its nature. The more one dwells into simple fact, the more the ground beneath one seems to shake. Even knowledge belonging to the realm of knowledge looses its absolute certainty, its irrefutability, for it is also derived from human’s induction. As far as induction goes, it is open to doubt no matter how tiny the probability.

-

The discussion on the truth alone is worth the entire book. Elusive a concept as it is, Russell’s treatment of the truth as a property of a belief (stated fact) is illuminating in its simplicity. He considers truth as the correspondence with an independent fact, and that the fact in question is expressed as an ordered relation among a set of constituents (terms). In logic terms, that fact is a proposition, and its existence in reality (independent of the observers) implies its truth. An example here is the statement: A believes that B loves C. This statement is true, or A believes truly, if there exists a relation Believe(A, Love(B,C)).

-

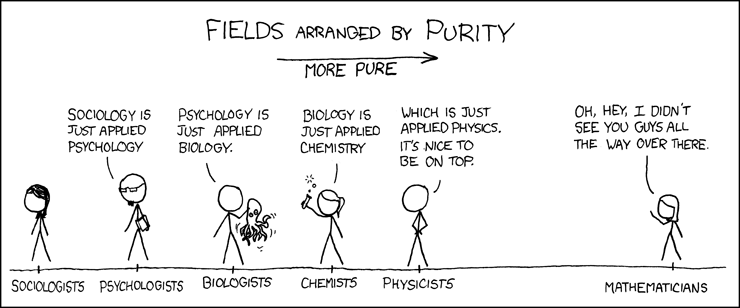

The values of philosophy lie in its questions. For some people, entertaining such questions are like taking food for their minds. However, as a discipline, philosophy contributes only indirectly to society, i.e. its impacts can only be vicariously felt. For philosophy does not seek answers, and as soon as the possibility of answers are at hand, it morphs into science. Thus every branch of science owes its methods to philosophy, which is the purest of all.

In the thoroughly contrasting of style, Frederick Nietzsche’s The Gay Science is as lyrical, as rhetorical, as dangerous as it is thought provoking. Written in German, it has been translated into English more than once. The version that I settled upon after few skimmings at other translation is the one published by Cambridge Press University. There is no doubt that the translators, Nauckhoff et al., deserve plenty of credits for the beautiful realization of Nietzsche’s ideas into English. Nietzsche would have approved.

It would be challenging to place this book in one existing category of fiction or non-fiction. Clearly it is not a fiction, but voice behind the text clearly takes a life on its own. And what a life it is, what a range of emotion, what a sense of observation, what a height of perspective, what a depth of conviction. At the same time, it is clearly beyond any non-fiction texts I have encountered. More than a collection of essays, for some of the most emphatic essays are merely few sentences in length. The topics change at dizzying pace, just enough for us readers to glimpse at the depth of a truth, to regard existing truths with enough suspicion. The author himself acknowledges at the end that he does it deliberately, that he deals with his topic like he takes a cold bath: fast in, fast out. But for the arguments that this approach is not the right way to get to the depths, he is dismissive, saying that the opposite, i.e. brooding on the topics for long time does not guarantee depths either. There are truths, he says, too shy that one must catch them by surprise, or not at all. This line of reasoning pervades the text: a seemingly contradictory fact (contradicting common knowledge) is stated, then the argument goes that the status quo does not always hold up, and hence the opposite must also be possible. The truth and untruth must exist at the same time. It is exciting, on the one hand, to see a new side of a problem. But at the same time, readers of his work feel rather unsatisfied, for he leaves open the questions as to the nature of this newly revealed side. Like discovering an ancient book which details tremendous treasure lying hidden in an island in the Pacific, but the actual maps are either missing or suffer damage beyond repair. It is like reading a paper having only the Introduction.

Among over 300 little essays, there are quite a few resonating ideas. Written in the 19th century, these ideas are astoundingly as relevant today as they are over a hundred year ago.

-

Suffering is good for the soul. Evils are required for the human race to progress. Nietzsche writes (or is translated) beautifully in support of these uncomfortable, morale-laden propositions. He brings in pictures of tall trees achieving their heights only by embracing stormy weathers, of crop fields needing to be ploughed to be fertile. It would not come as a surprise if Nietzsche wasn’t a strong opponents of wars and crimes against humanity. Neither would one doubt that evil men could take after revere Nietzsche’s philosophy, could take his philosophy to dignify their actions. Revolutionary ideas and extremely dangerous ideas are kept apart by a very thin line here.

-

God is dead, morality is dead, and preachers of morality are villainous. Nietzsche reduces religion and religious teachers to their weakening of the souls, because they assume that their followers are too weak to have free will of themselves, that they are dependent of meaning and purposes to make life worth living. Nietzsche rejects the premise that one must avoid sufferings, must eschew sins in order to be virtuous and to be loved. And with the society starting to embrace suffering, starting to reflect and ask questions on the love of God, Nietzsche makes his most famous observation, that “God is dead, and we have killed him”.

-

He praises the values of science, which dispenses with morality and religion, and which despite its seemingly random process holds up remarkably well against scrutiny. He equally praises the suffering of a scientist, of a thinker, who is

devoted to their causes, and who suffers immensely because he strives to be master of his craft. And suffering, to Nietzsche, is a pre-requisite to become a master of anything. -

To a thinker, life is a great experiment. His actions are merely experiments, and their successes or failures are merely outcomes of the experiments: merely answers. As such, such outcomes should be devoid of feelings. Anxiety, disappointment, happiness over the results of the experiments should not be the thinker’s concerns. His suffering is merely against the enormity of knowledge, over the physical strains suffered in the path toward knowledge. This view encourages a scientist to try out new things, to not be afraid of failures, i.e. to experiment. The idea of taking things objectively in science, never aiming for perfection, and not relinquish oneself to emotions, is not new. But Nietzsche’s proses speak more directly and loudly to me than ever before. And carrying with them fresh perspectives, how they sooth the mind.

Happy new year! May 2017 bring more content to this humble page.