Subtle Details in PBFT

Almost a year has gone by since I sat down and decided to take on Byzantine fault tolerance protocols, starting with its poster child PBFT. Despite countless reprintings and re-readings the OSDI’99 version of the paper, I never stop learning new things at every reread. This is party exacerbated by the fact that Hyperledger Fabric, an open source permissioned blockchain system, contains a Go implementation of PBFT which serves as the basis for truly understanding the protocol. Discrepancies between the implementation and the paper bring the protocol’s internal intricacies out to the surface. The following summarizes few subtleties I discovered.

Network failure model

Byzantine fault tolerant protocols tolerate at most \(f\) Byzantine failures. In a distributed system, however, there are two types of failures: node and network. It is important to distinguish them, especially since they determine guarantees about the protocol’s safety and liveness.

Node failure means a node (or server, peer, entity, etc.) behaves arbitrarily. This captures the strongest adversary model. A network failure refers to network partitions which can last for an unbounded amount of time. It can be quantified as the number of nodes being isolated from the rest of the network, although they can still communicate with each other.

Given this distinction, what are being counted toward \(f\)? In PBFT

-

\(f\) refers to node failures. The protocol guarantees safety upto \(f\) node failures. Safety is independent of network failure. That is, even if the network is severely partition, namely more than \(f\) nodes are isolated (but across all partitions there are still fewer than \(f\) node failures), the protocol is still safe.

-

However, liveness is only guaranteed with fewer than \(f\) total failures, i.e. counting both node and network failures. This means at least \(2f+1\) nodes must be reachable.

Note that safety being independent of network failures is a strong guarantee, and it is common in most variants of PBFT. Not until Liu et al. recent work, namely XFT, is it relaxed in a way that separates out node and network failures.

View change

View changes remain the most complex part of PBFT, and it is also a huge factor determining performance, if not liveness of the system. I am still far from fully understanding view change, but try anyway to explain the intuition behind its complexity. There are significant difference between MAC-based and signature-based protocols, as will be made clear later. For this, I will assume that messages are authenticated with signatures.

View change being complex, it should only be triggered by non-faulty nodes whose timers expired. It means a normal node, whose timer has not expired, will not join the protocol unless it has sees that \(f+1\) others have. Once enough nodes voted for view change, the new leader must decide on the latest checkpoint and ensure, among other things, that non-faulty nodes are caught up with the latest states, which may involve re-committing (prepare, commit, but no execution) previously executed requests in the new view. During view change, no requests are processed.

View change explains the need for COMMIT phase

View change effectively gives a new node the power of assigning sequence number to requests. It must then ensure that the new leader does not use old sequence numbers for new requests, either deliberately or gamed into it by faulty nodes. The safety property of PBFT states that:

… the algorithm provides safety if all non-faulty replicas agree on the sequence numbers of requests that commit locally

What it implies is if \((n,m))\) is committed at a non-faulty node in view \(v\), the tuple \((n,m')\) must not be committed in view \(v' > v\) at any other non-faulty replica. The following problem doesn’t apply to non-Byzantine settings which as a consequence needs only two phases (corresponding to Pre-prepare and Prepare).

-

In view \(v\), a non-faulty node \(A\) receives \(2f+1\) Prepare certificates for a sequence number \(n\) attached to message \(m\). It correctly assumes that \((n,m)\) is ordered the same way by \(f+1\) non-faulty nodes, including itself.

-

Thinking that \((n,m)\) has been finalized, \(A\) executes \(m\) and replies to the client. This response is backed up by \(f\) fake responses from the adversary, convincing the client that \((n,m)\) was committed.

-

View change happens. The new leader did not see all \(2f+1\) Prepare certificates. Neither did the other \(f-1\) non-faulty nodes. This could happen due to network partition or effected by the faulty nodes. For those nodes, \((n,m)\) was not prepared and the sequence number \(n\) is deemed invalid.

-

The new leader was elected, and it manages to convince other nodes that the last Prepared valid sequence number from view \(v\) is \(n-1\) by collecting enough votes of Prepared certificates from all nodes except \(A\). It then moves the \(v+1\) and start assigning \((n,m')\) for \(m' \neq m\), which is eventually committed. Safety is violated as the result, since the client see both \((n,m)\) and \((n,m')\).

The solution to this is to make sure \(A\) sees that enough other nodes also received \(2f+1\) Prepare certificates. Only then does it execute the request and reply to the client. More specifically, a node sends out Commit certificate once it collects \(2f+1\) Prepare certificates. And it considers \((n,m)\) committed only when it receives \(2f+1\) Commit certificates, i.e. there are \(2f+1\) nodes each of which sees \(2f+1\) Prepare certificate. Now, during view change, the new leader cannot convince other nodes that the latest sequence is \(n-1\), as there will be at least 1 non-faulty node joining the view change with Prepare certificate for \(n\).

View change is expensive

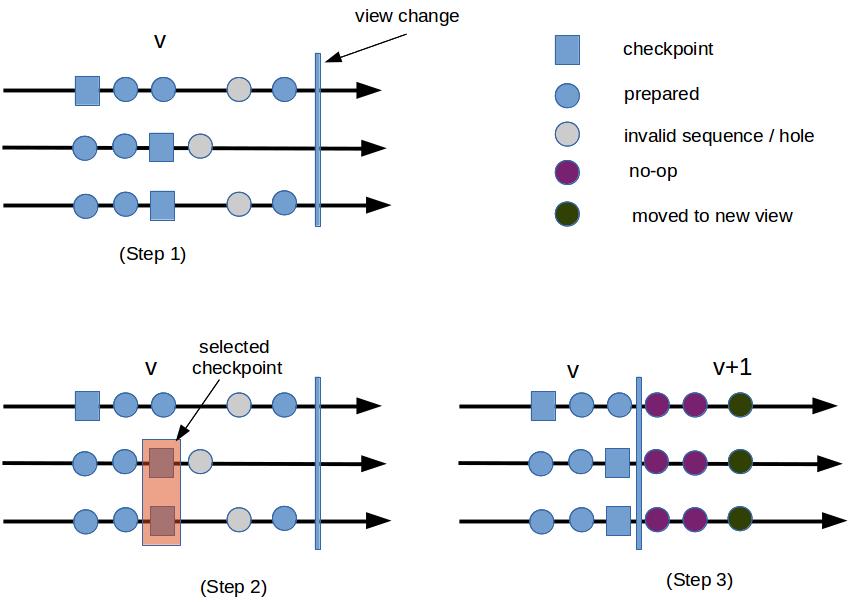

The figure above illustrates high-level steps taken by replicas during view change.

Step 1. Before view change starts, a node’s state consists of:

-

Checkpoints (squares) which are persisted states.

-

A Prepared certificate (blue circle) for each sequence number \(n\) greater than the lowest checkpoint. Some of these sequence numbers have committed (if \(2f+1\) have broadcast Commit message), some have not. Regardless, the same number will not be assigned (and eventually committed) in the new view with a different message.

-

Invalid certificate (grey circle) for sequence number are Pre-prepared but no matching \(2f+1\) Prepare certificates. This may happen due to network failures or the leader being faulty (it sends conflicting Pre-prepare messages to different nodes).

Step 1.5. Each node that wants to trigger view change broadcasts \(<VC,..,n,C,P>\) where \(n\) is the sequence number of its latest checkpoint, \(C\) is the checkpoint certificates (containing \(f+1\) certificates from other replicas), and \(P\) is the Prepared certificate containing \(2f+1\) Prepare messages received from other replicas (and one from itself).

The new primary waits for \(2f+1\) of VC messages, which makes sure that committed sequence numbers from previous views are included in at least one prepared certificate in one VC message. A sequence \(n\) is committed at a replica if it the replica has proof that at least \(2f+1\) replicas have the corresponding prepared certificate. Quorum intersection implies at least 1 non-faulty node is included in the \(\{VC\}\) set received by the new primary, there is at least one VC message whose \(P\) contains a prepared certificate of \(n\). This way, any prepared sequence numbers in the previous view will be visible to replicas in the new view, meaning that the same sequence number will not be re-used in the new view.

Step 2. The new primary selects the largest checkpoint sequence \(n\) from \(\{VC\}\). This checkpoint is stable (stable checkpoints are discussed in the next section), thus it can be reliably fetched from the network.

Step 3. Starting from \(n\), the primary identifies the largest sequence number \(H\) from the previous view that has a Prepare certificate, i.e. \(H\) is included in the \(P\) component of a VC message. Then, for every sequence \(s\) such that \(n < s \leq H\):

-

If there is a Prepared certificate for \((s,m)\), start consensus for \((s,m)\) again by broadcasting Pre-Prepare message for the tuple. This is to advance the sequence number in the new view past ones that have been (or are going to be) committed in the previous view. In effect, the replicas go through Pre-prepare, Prepare, Commit phase again for \((s,n)\), even though the replicas remember what they executed and ignore re-execution. They also remember if they have sent replies back to the client, and do not do it again in the new view.

-

If there is no Prepared certificate for \(s\), it becomes a hole in the sequence number line. The primary fills this hole with a no-op request. Recall that holes happened when the requests are not prepared successfully due to network partition or the primary being faulty.

The collection of messages (step 1.5) and re-execution of previous requests (step 3) are communication bound. View change is expensive and to be avoid as much as possible. Nevertheless, it is essential to guarantee liveness, and completing it quickly is so important that the replicas stop accepting non-view-change related messages during the protocol.

The role of prepare certificate \(P\) during view change

Recall the safety property states that if \((n,m)\) is committed locally in a view \(v\), there will not be a committed \((n,m')\) in a later view \(v' > v\) for any \(m \neq m\). Step 1-3 above guarantee this property hold. The key idea is that if \((n,m)\) is committed in \(v\), the primary must pick it and pre-prepare the same tuple in the new view. The view change protocol uses Prepared certificates \(P\) to make sure the primary picks \((n,m)\). But, is \(P\) necessary, in other words, can the primary uses Commit certificate instead? If not, does the primary only pick the sequence that was committed locally at one replica?

- Can the primary use commit certificate during view change? Instead of \(P\) in the view change message,

suppose every replica include \(C\), their Commit certificate. Next, the new primary only choose \((n,m)\) if

it is included in one Commit certificate, and \(null\) otherwise. Three scenarios arise:

- \((n,m)\) has not been committed at any replica in the previous view. The primary will pick \((n,null)\). No safety violation happens here, but \(m\) is lost. The client may eventually time out and resend it, which is bad for liveness (though not a violation of liveness).

- \((n,m)\) was committed at some replicas whose view change message reach the new primary. In this case, the primary will pick it, and safety is ensured. The adversary cannot fake certificate content, therefore one certificate is sufficient proof that the tuple was committed.

- \((n,m)\) was committed at some replicas whose view changes message do not reach the new primary. In this case, the primary will pick \((n,null)\) for the new view, therefore violating safety.

So it does seem that Prepared certificate is necessary to achieve safety. Which then brings us to the next question.

- Does new primary pick only the sequence that was committed? Or, does it pick \((n,m)\) if and only if

\((n,m)\) was committed? The primary picks any \((n,m)\) that was in a Prepared certificate, there are two

cases:

- \((n,m)\) was committed: then it is safe.

- \((n,m)\) was not committed. This happens, for example, when a node \(A\) received \(2f+1\) Prepare certificates and sent out Commit message, but network faults occurred that cause all other nodes not receiving enough Prepare messages to form Prepared certificate. The primary picks the same tuple as in the previous view, therefore it is safe.

Similarly, when the primary picks \((n,null)\), there are two cases:

- \(n\) was not successfully prepared.

- It was prepared by some nodes whose view change messages do not reach the new primary.

Regardless of what the primary picks, the worst it could happen is that a message prepared in a previous view is re-prepared again with a different sequence number in the new view. However, it happens only when the message was not committed, i.e. safety is guaranteed.

Signatures vs. MAC

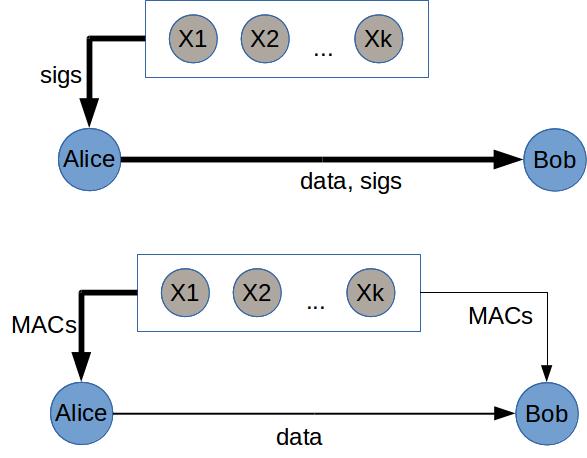

Signatures are generated with a private key and verified with a public key. In contrast, MACs are generated using a shared secret. From a system’s perspective, they offer different properties:

-

Signatures are often longer (RSA, DSA) and expensive to compute. MACs are cheap.

-

Signatures are publicly verifiable, MACs are only verifiable with the secret key. An important consequence is that signatures are irrefutable: once Alice signed a message, anyone will be convinced of its authenticity. On the other hand, MAC cannot be used to prove authenticity, i.e. once Alice generated a MAC for a message with Bob, Bob cannot use this as evidence that Alice has signed. A third party, Veronica, cannot verify that the MAC is correct, since he does not know the secret key. Even Bob shares with Veronica the secret, the latter still does not know whether the MAC is created by Bob or by Alice.

The first property was what came to my mind when reading a passage in the original paper about alternative implementations of the protocol. I had quickly dismissed it as merely an implementation choice. I had a second chance of re-examining it when reading Byzcoin (by Kogias et. al. in Usenix Security 2016), which has one optimization to reduce communication overhead by replacing MACs with signatures. But not until reading Castro’s PhD thesis did I learn the far-reaching implication of the choice between MACs and signatures. No surprise that the thesis devotes individual section for each of them.

High-level idea. During view change of PBFT, the new leader has to prove to other nodes that it has the right to trigger view change, by bundling view-change requests from other nodes. Furthermore, a node must prove to another that it has a certain checkpoint, or is able to fetch another checkpoint. This proof is needed for selecting an initial state from which the new view begins. How to generate such proofs? Using signatures, a node can collect a set of signed statements from others, i.e. certificates containing the needed information. It can then show to another as proof that other nodes have had the information. Since there is no way to forge signatures, these certificates are sufficient. However, with MAC, the verifying node relies on non-faulty nodes to broadcast the same information. That is, rather than \(A\) present to \(B\) a certificate as proof of authenticity, it counts on \(B\) to seeks verifying information from other nodes. The challenge is for \(A\) to be certain that \(B\) will succeed in obtaining such proof.

Stable checkpoints

Checkpoints are essentially persisted states. They serve two roles: garbage collection and state transfer. When a checkpoint is adequately replicated, previous states including messages and certificates can be discarded. During a view change, a checkpoint is selected as the most recent states most nodes agree on. From that, some nodes need to catch up (by transferring states from another node) and some requests need to be re-committed in a new view.

To fulfill its roles, a node collects checkpoint certificates from others, and considers a checkpoint \(c\) stable when it is sufficiently replicated and can be reliably retrieved by any other node.

-

With signatures, \(f+1\) certificates are sufficient to form a stable certificate. The nodes generating these certificates cannot deny that they have the checkpoint, because they have signed them. And \(f+1\) ensure that at least one of them is reachable.

-

With MACs, \(2f+1\) certificates (MACs) are needed to form a stable certificate. This is to ensure at least \(f+1\) non-faulty nodes store the checkpoint, and later on these \(f+1\) can send the same information to the verifier to prove the existence of the checkpoint. Suppose Alice collects only \(f+1\) certificates (one from itself) before considering the checkpoint \(c\) stable. The other \(f\) can be controlled by the adversary. Later on, Bob wants to retrieve \(c\), but the adversary present \(f\) invalid checkpoints. There is no way for Bob to determine which one is correct (a similar problem in quorum systems without data authenticate — see the post on quorum). Then, the checkpoint is essentially lost. Any number smaller than \(2f+1\) is not enough, because the adversary, controlling \(f\) certificates, can convince the verifier to accept invalid checkpoint.

Discrepancy notes. The OSDI version of PBFT described stable checkpoints in MAC mode (\(2f+1\) certificates), despite it saying in the early part that it is in signature mode. Only later in the paper is it mentioned that the description is actually for MAC mode.

View change

This excerpt from the paper is an understatement:

We were able to retain the same communication structure during normal case operation and garbage collection at the expense of significant and subtle changes to the view change protocol.

A key step during a view change is for the primary to reliably pick messages from the previous view to pre-prepare again in the new view. Signatures provide a means to verify that \((n,m)\) was truly prepared by some replicas, therefore if it was committed in the previous view it will be picked. Without signatures, verification is more complex. Each replica must verify by itself by collecting \(f+1\) messages from other replicas, as opposed to checking one signed message.

The new view change proceeds as follows:

Step 1. The replica \(r\) collects message into \(PSet\) and \(QSet\), which are then included in the view change message:

- \(PSet\) contains tuple \((n,m,v)\) that are prepared at \(r\) at view \(v\).

- \(QSet\) contains tuple \((n,m,v)\) that are pre-prepared at \(r\) at view \(v\).

Note the difference between \((PSet, QSet)\) and \(P\). The former contains local information; the latter bundle certificates from remote replicas as well. Without signatures, remote messages are of no use.

Step 1.5. The primary waits for \(2f+1\) view change messages. Previously, this quorum ensures that committed messages are included in at least one view change message. Here, it also ensures that there will be a weak certificate of \(f+1\) messages from the non-faulty nodes which can serve as proof that some information is stored.

Step 2. The primary picks the starting state of the new view by choosing a stable checkpoint with sequence \(s\) which is backed by \(f+1\) view change messages.

Step 3. The primary picks message to pre-prepare as follows:

- It picks \((n,m)\) if \(n\) has not been garbage collected by \(2f+1\) replicas, it is included in a \(PSet\), and there are \(f+1\) matching \(QSet\) messages.

- It picks \((n,null)\) if there are \(2f+1\) \(PSet\) messages that do not have \(n\).

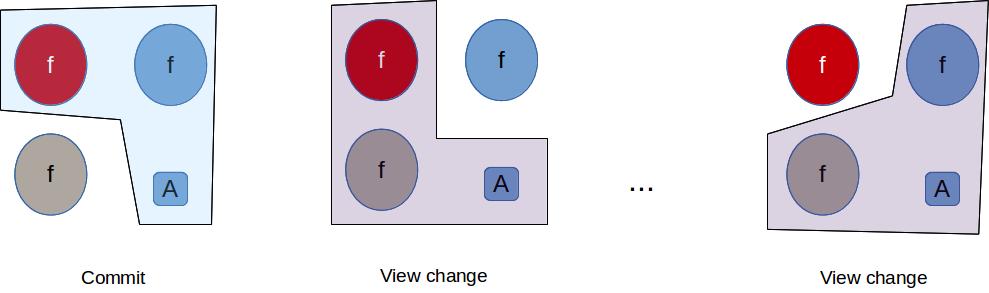

Step 3 is very confusing, and I am still unsure if I understood the reason behind it. Here is what I think I understand, based on an example illustrated in the figure below.

In this example, Byzantine nodes are marked red, non-faulty nodes that took part in the commit phase are blue, and the other non-faulty, partitioned nodes are in grey. Let’s first see why step 3 is safe. If \((n,m)\) is committed in view \(v\), it will be picked by the primary.

- \((n,m)\) was committed at \(A\), thus there are at least one \((n,m)\) is seen by the primary during view change. But the adversary can also present \((n,m')\) during view change. How do the primary pick the correct one?

- The condition of \(f+1\) matching \(QSet\) message solve ensures that \((n,m')\) will not be picked. In the figure, the first view change cannot pick \((n,m)\) either. There may be many view changes before it can be satisfied by a quorum of \(2f+1\) non-faulty nodes.

Notice that with only \(2f+1\), the primary may not be able to pick any message to prepare — both conditions are not met. As the result, the view change may time out. The paper makes the assumption that eventually a quorum of non-faulty nodes is available, then the primary will pick either \((n,m)\) or \((n,null)\).

Recall that during view change protocol with signatures, the primary also pick \((n,m)\) that was prepared at some replicas but not yet committed. The same happens here:

- \((n,m)\) was prepared at \(A\), meaning that it must be pre-prepared at \(f+1\) honest nodes. Note that \((n,m)\) only have to appear once in \(2f+1\) view change messages, similar to the protocol with signatures.

- \(f+1\) matching \(QSet\) will eventually be satisfied, maybe after many view changes. Then, \((n,m)\) is picked for the new view.

It also happens that a prepared message in view \(v\) may be lost. Suppose \(A\) receives a Prepared certificate for \((n,m)\), but all others do not. During view change \(A\) was isolated, and there was no \((n,m)\) found in \(PSet\). The primary then picks \((n,null)\).

In summary, view change without MACs is safe. It may be slower in making progress, but it has the same eventual liveness as with signatures.

Discrepancy notes. Even Castro’s thesis doesn’t contain a formal model and proof for the MAC-based protocol. Hyperledger’s implementation of view change follows the MAC-based protocol, except that view change messages are signed, obviating the need for each replica to collect view change messages directly from each other. In other words, the primary can collect all \(2f+1\) view change messages and bundle them when sending new view messages to replica.