Quorum Systems

During the course of my continuing struggle with PBFT, which deserves its own blog entry, I caught a reference to a term dissemination quorum. Previously content with the explanation of quorum being a fanciful term for describing a subset of nodes, of which the most common type is majority quorum, I followed the references rather reluctantly. And boy was I served a big humble pie.

The idea of quorums and quorum system dates as far back as the time when computer failures were recognized as a real problem. It exists before FLP, before Paxos, and by extension, long before PBFT. The reason why it rarely surfaces can be attributed to its theoretical nature. And similar to FLP, its popularity was eclipsed by the popularity of later work that take the theoretical results and make them more practical. Studies of quorum systems pave the way for Paxos, PBFT and many other work in making distributed systems tolerant to failures. The paper being dissected in this post is Malkhi et. al.’s “Byzantine quorum systems” published in 1997 (2 years before Castro et al.’s PBFT).

What is a quorum?

Given a set of node \(U\), a quorum system is a set of subsets of \(U\) (or quorums) in which any two quorums intersect. More formally, \(Q\) is a quorum system defined as \(Q \subseteq \mathbb{P}(U) \ \wedge \ \forall q_1, q_2 \in Q [ q_1 \ \cap \ q2 \neq \emptyset ]\)

Examples

A set of majority subsets in \(U\) is a quorum system. In fact, it is the most common instance of quorum systems, found most often in fault-tolerant protocols. Paxos, in particular, relies on quorums of size \(f+1\) in network of \(2f+1\) nodes. However, there are other examples whose quorums are not majority set.

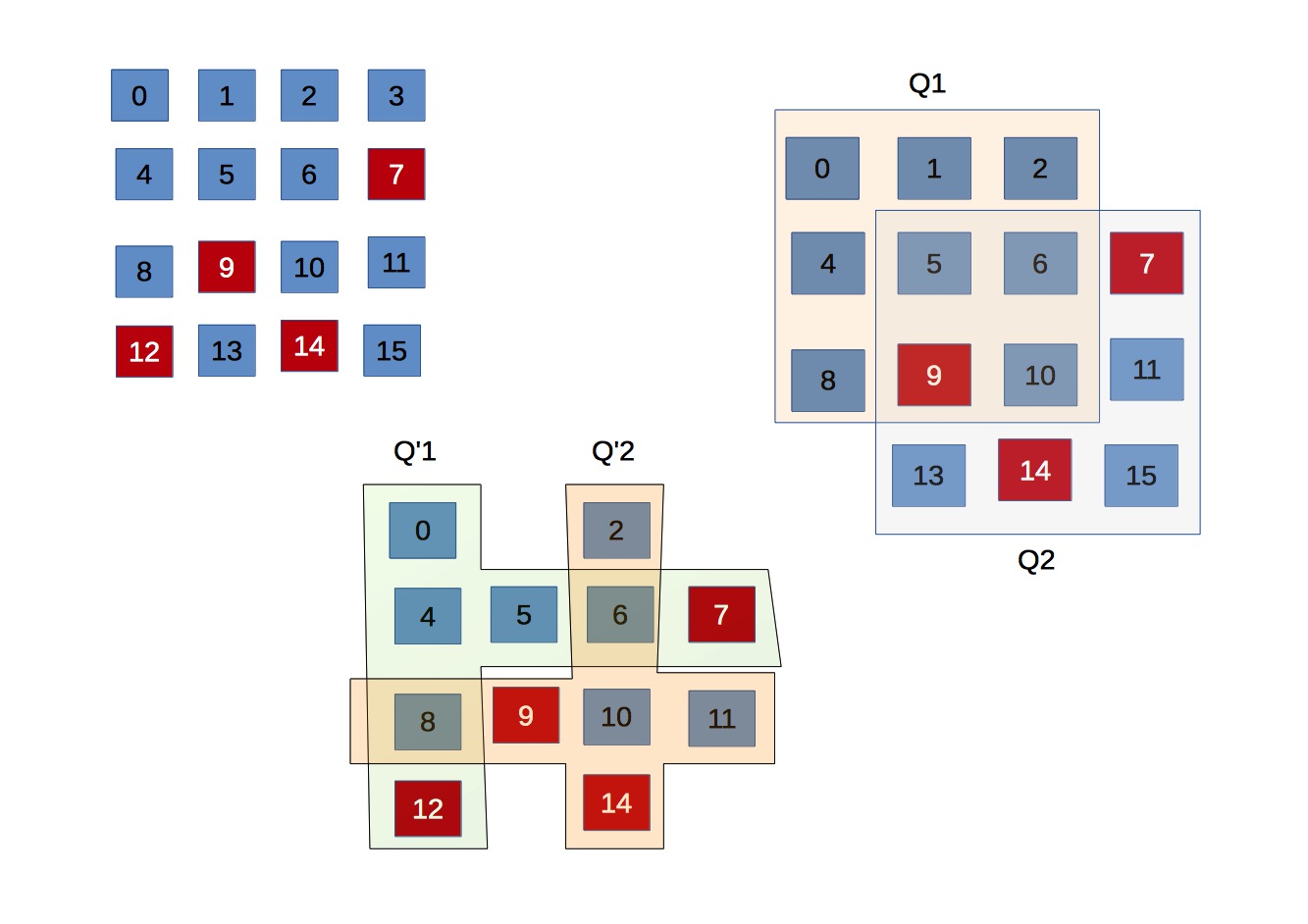

The figure above illustrates two quorum systems derived from \(U\) of 16 nodes. The first system, called majority quorum, is made up of majority-set quorums wherein each quorum is of size 9. The second, called grid quorum, consists of quorums of size 7, but each pair always intersects at least 2 nodes. There are \(|U|\) quorums in this example, where \(q_{ij}\) comprises node in row \(i\) and column \(j\).

Why quorums are useful

Quorums are useful in the context of replicated systems, be it a replicated storage or a more general replicated state machine. A quorum serves as a representative of the entire system, and it can service client requests on behalf the system. It means that a client needs only to contact the nodes in a quorum, as opposed to all the nodes. And thanks to quorum intersection, updates made in one quorum can be made consistent by propagating them to the rest of the network. Two immediate benefits are:

-

Performance via load balancing: two client requests may be served concurrently by two quorums, and the busy nodes can be opted-out of the serving quorum until its load goes down.

-

Fault tolerance: the system continue to work even when there are node failures, as long as a quorum is still available. Original quorum systems were designed for crash-failure, which exploits quorum intersection to keep failed nodes up-to-date once they are recovered. In Byzantine settings, that faulty nodes can infiltrate quorums requires more complex reasoning and imposes more conditions on quorums — exactly what Malkhi et. al. set out to do in their paper.

Quorum systems

Properties of a quorum system can only be discussed under specific application model, and under specific failure model. As discussed below, these models are very abstracted, and therefore rather simplistic. One reason may be that when the idea was first proposed, large-scale distributed systems and their glorious complexity did not yet exist, thus these models could be considered realistic. Regardless, the abstract models make it easy to analyze the system formally.

APIs

A quorum system exposes shared read/write register over multiple client. In today’s terms, it is treated as a remote storage with read/write APIs accessible by many clients. Let \(Q\) be a random quorum; it truly doesn’t matter which quorum, only that it is of a certain sizes.

-

Write: the client queries all nodes \(n in Q\) for a set of timestamps \(\{t_i\}\). It then picks \(t = max(\{t_i\})\) and computes \(t' > t\) in a way that two clients’ picks are not the same. Finally, it sends the data to \(Q\) and waits until it is acknowledged by all nodes in \(Q\).

-

Read: the clients queries \(Q\) for a set of \(\{(v_i, t_i)\}\). It runs this set through a function \(Result(.)\) which returns the correct value.

The write API, in practical terms, is not very efficient because it is interactive, requiring many rounds of communication. Modern storage systems, for instance, incur only 1 round of communication by dedicate primary nodes to serve requests of specific ranges. The quorum write API is simple, but more importantly it removes additional trust assumed on the primary nodes. As for read API, details of $$Result(.)$ depends on assumptions about data property, namely if the data is tamper proof (integrity protect).

Safety property is defined as read returns the latest write, providing that there is no concurrent write. The first phase is similar to cache coherency, but the second imposes a condition that renders it a weaker guarantee. I will come back to this later.

Unauthenticated Data - Masking Quorum

Suppose there are up to \(f\) Byzantine nodes, and they can lie about what data they store. In particular, these nodes may return \(\{(v_i, t_i)\}\) that were never sent by the client. In other words, updates by the client are not integrity protected, which happens when client identity is not known (no PKI certificate).

Now what would it take to achieve safety in this case, with up to \(f\) failures. Let \(B\) be the set of \(f\) faulty nodes. Then,

- The correct tuple is \(C = (t_c, v_c) = Q_w \cap Q_r \setminus B\).

- The set of out-of-date tuples is \(O = \{(t_o, v_o)\} = Q_w \setminus (Q_r \cup B)\).

- The set of arbitrary tuples generated by the adversary is \(A = \{(t^*, v^*)\} = Q_r \cap B\)

The client can distinguish \(C\) from \(O\) because the former has higher timestamps. However, \(A\) may also has higher timestamps, because the faulty nodes can forge tuple without being detected. Thus, the client must be able to identify \(t_c\) from \(t^*\). Because \(|A| \leq |B|\), one way to do it (here I’m not sure if it’s the only way) is to make sure that \(|C| > |B|\). More specifically:

\[|Q_w \cap Q_r \setminus B| > |B| \leftrightarrow |Q_w \cap Q_r| > 2.f\]Any quorum system satisfies the above condition for any pair of its quorum is called masking quorum.

Essentially, a masking quorum system guarantees any two quorum intersects at at least \(2f+1\) nodes. One example is a system of \(4f+1\) nodes wherein a quorum consists of \(3f+1\) nodes. It took me a while to understand the intuition behind the intersection size of at least \(2f+1\).

-

First, suppose the quorum intersects at \(f\) nodes. How would the client identify which response tuples are correct? It simply cannot. Without failure, the correct tuples are \(f\) tuples with the same, largest timestamp. But faulty nodes can forge these tuples.

-

Second, suppose the intersection consists of \(f+k\) nodes, i.e. at least one correct node is in the intersection. The client must choose from a subset of of \(f+k\). But it cannot use any subset smaller than \(f+1\), because no matter what the condition for selection is, the faulty nodes can satisfy it by forging tuples. So the selection must based on \(f+1\) tuples being equal.

- For \(k < f+1\), the faulty nodes can make sure that this never happen because it controls up to \(f\) of them. As the result the read operation fails — failing is not really tolerating failures (the quorum is still reachable, the number of failures is within permitted threshold, yet it fail!).

- With \(k \geq f+1\), however, it is possible to correctly identify the set of \(f+1\) tuples of the same timestamp as coming from the non-faulty nodes. The faulty nodes cannot form such a set.

Thus, in order for the client to identify correct tuples, the intersection size is at least \(2f+1\).

Authenticated Data - Dissemination Quorum

In a masking quorum system, the client has no means of checking if \((t,v)\) returned from a node in a quorum was a genuine tuple put their by a previous client. Because of this, quorums intersecting at \(f+1\), for example, are unable to mask Byzantine failures

Now, suppose \((t,v)\) is verifiable by the client performing read, which could be achieved by signing the tuple with the write client’s public key (assuming it comes with a PKI certificate), or by appending a MAC for which both clients know the key. With this, the adversary cannot response to a read operation with arbitrary tuples without being detected, although it can reply with out-of-date tuples. Let’s go through the reasoning about quorum intersection

- The correct tuple is \(C = (t_c, v_c) = Q_w \cap Q_r \setminus B\).

- The set of out-of-date tuples is \(O = Q_w \setminus C\).

The client can easily identify the correct tuple as one with the largest timestamp. For this, \(C\) is a non-empty set, i.e. \((Q_w \cap Q_r) \setminus B \neq \emptyset\). Because \(|B| = f\), this condition is the same as \(|Q_w \cap Q_r| \geq f+1\). A quorum system where that condition holds is called a dissemination quorum. It guarantees that any two quorum intersects at at least \(f+1\) nodes. One example is the PBFT quorum, with \(3f+1\) nodes and quorum size of \(2f+1\).

Intuitively, the intersection must be more than \(f\) nodes. Unlike in masking quorum system, the adversary cannot forge any tuple \((t^*, v^*)\) because it cannot produce correct signature or MAC for that tuple. However, it can replay tuples with old timestamp, thus successfully discarding new updates. A read operation in this case will not see the latest write. With \(f+1\) nodes in the intersection, however, there is at least 1 correct node that responses with timestamp \(t_c\). The adversary responding arbitrarily can be detected as faulty and exclude from the selection (and more action can be taken to isolate that node). As the result, it can either reply with the same tuples, i.e. not behaving badly, or with an old tuple with timestamp \(t_o\).

Quorum vs. Paxos vs. PBFT

A quorum system serve as the base from which consensus protocol such as Paxos and PBFT are built. Quorum’s safety property is necessary to achieve that of Paxos and PBFT. Let’s examine how they differ more closely.

Size of the intersection. PBFT uses dissemination quorums: \((2f+1)\)-node quorums to mask \(f\) faulty nodes in a \((3f+1)\)-node network. With crash failures (Paxos), a quorum system’s safety is guaranteed as long as \(Q_w \cap Q_r \neq \emptyset\), or \(|Q_w \cap Q_r| \geq 1\). For write to be successful, it also requires \(|Q_w| > f\) so that at least one update survive. As a result, the condition to mask \(f\) crash failures is:

\[\forall Q_1,Q_2\,.\, |Q_1| \cap |Q_2| \geq 1 \cap |Q_1| \geq f \cap |Q_2| \geq f\]Paxos uses quorums satisfying the above condition: quorums of \(f+1\) nodes in a \(2f+1\)-node system.

Safety semantics. Recall quorum’s safety is the following:

Reads see the latest writes, provided there are no concurrent writes

Note the emphasis, which implies that two reads may return different values when there are concurrent writes. Suppose the latest write has \(X=3\), and a write operation is updating \(X=4\). The write is sending updates to quorum \(Q\) and half of the nodes, say \(Q_h\) in the quorum have received updates. Two concurrent reads are contacting two quorums \(Q_1\) and \(Q_2\), where \(Q_1 \cap Q \subseteq Q_h\), but \(Q_2 \cap Q \cap Q_h = \emptyset\). The first sees \(X=4\), but the second sees \(X=3\) since updates have not propagated to the intersection.

Both Paxos and PBFT are design to prevent the scenarios like above.

Reads see the latest writes.

The protocols go through multiple phases to make sure that all quorums see the latest commit or nothing at all. PBFT, in particular, executes Pre-prepare, Prepare and Commit phase and only considers a write successful after all nodes in the quorum commit. After this, all reads will return the latest — same as a quorum system. But during the three phases (concurrent writes), reads will return the latest committed value, not the one being committed. This update atomicity makes it easier to reason about the system state, since it mirrors what is expected in a single-node system: before any write finishes, read returns the previous value. Technically a quorum system can be enhanced to have atomicity, by changing its APIs to obtain a global lock before any operation. However, implementing the global lock requires something like Paxos or PBFT.